It’s been one year since the U.S. government launched FedNow, its long-awaited real-time payments (RTP) system.

More than 70 other countries already had national RTP rails at the time and some, like Brazil, India, and China have seen huge adoption in the years since they rolled out their own infrastructure. At the time, I compared their experience with the uniquely fragmented banking landscape and entrenched card payment infrastructure in the United States to make 10 predictions for FedNow.

Those predictions were:

- FedNow would start a domino effect of RTP adoption, led by consumer use cases

- Mass network connectivity would take close to a decade

- FedNow would replace cash and checks, but not credit cards

- Person-to-business (P2B) account-to-account use cases would grow slowly, but steadily

- FedNow would offer an incremental improvement on payment infrastructure, not a paradigm shift

- Interoperability would be a prerequisite for any QR code renaissance

- Digital wallets would become the next battlefield in e-commerce and at the point of sale

- Authorized push payment fraud would rise

- Attracted by high speeds and low costs, consumers and small businesses would be quicker to adopt RTP

- FedNow would fuel cross-border money movement

A year on from FedNow’s launch, it’s time to check in on those predictions — some of which require more explanation than others. Let’s check through the quick ones first:

- FedNow early in a long process of replacing cash and checks — but not credit cards.

- FedNow is offering an incremental improvement on payment infrastructure, but not a paradigm shift.

- For now, we are still waiting for the mass domestic adoption of FedNow that would help it fuel increased international money movement.

Okay, let’s take a look at what we learned:

Mass connectivity will take a long time…

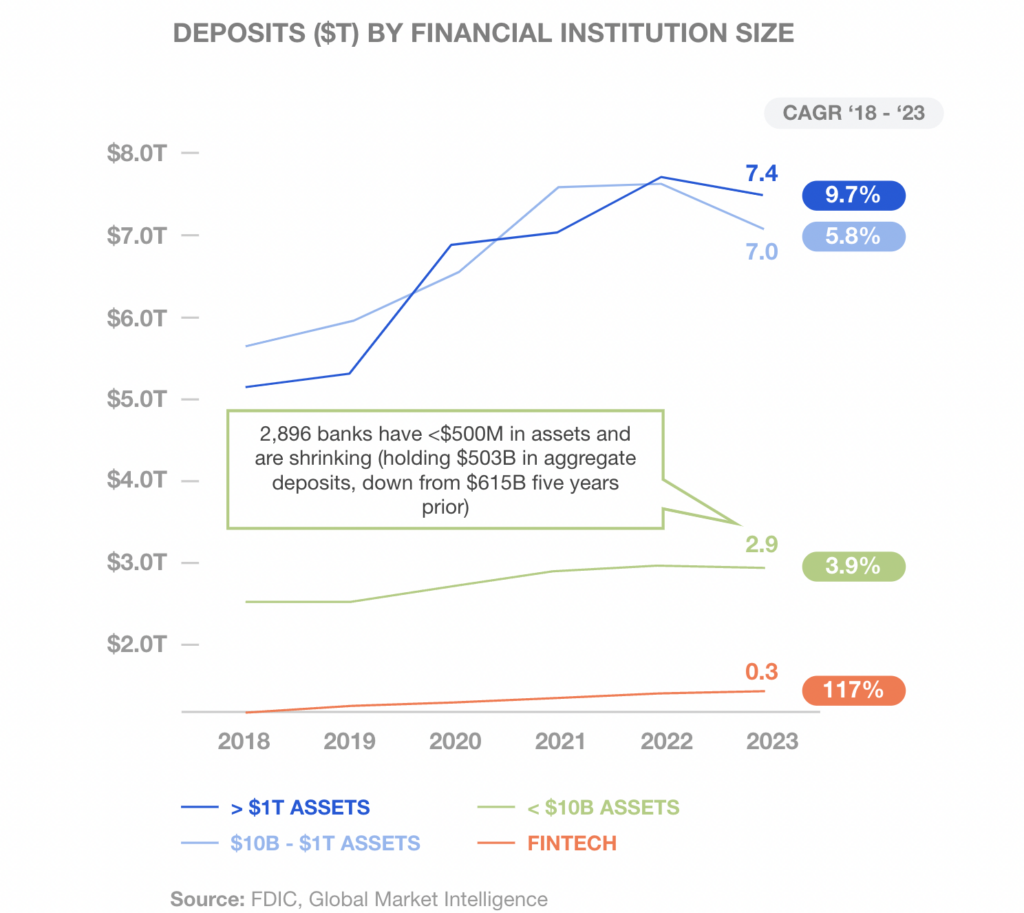

…But hopefully not too long. I recently participated in a Wharton FinTech Podcast interview with Nick Stanescu, who serves as Chief FedNow Executive at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. During our discussion, he shared that there are now close to 900 financial institutions live on FedNow, including banks and credit unions of all sizes across all 50 states. A year ago, that number was 35. However, remember America’s uniquely fragmented banking system: the country has almost 8,000 banks and credit unions. So while mass connectivity is still a long way away, hopefully this encouraging early adoption rate means we’re closer to five years away, instead of ten.

FedNow will start a domino effect of RTP adoption

As Stanescu pointed out in our interview, the majority of FedNow transactions fall under consumer use cases. Most of those have been account-to-account payments, the funding of digital wallets, and even earned wage access, where workers can access their wages the same day they earn them. Other exciting use cases include insurance payouts and emergency relief payments, typically lengthy processes which would happen instantaneously on FedNow rails.

Merchant incentives: Cost savings alone aren’t enough

Brazil’s Pix system has one of the most impressive RTP adoption rates in the world, and is predicted to account for 40 percent of the country’s online shopping transactions by 2026. There are a number of structural reasons for RTP’s success in Brazil relative to the United States, including differences in card payments infrastructure and the aforementioned banking fragmentation (or lack thereof — in Brazil, the top five banks account for 80 percent of total commercial assets, compared with 49 percent in the US). But there’s another structural difference we hadn’t initially accounted for: merchant incentives.

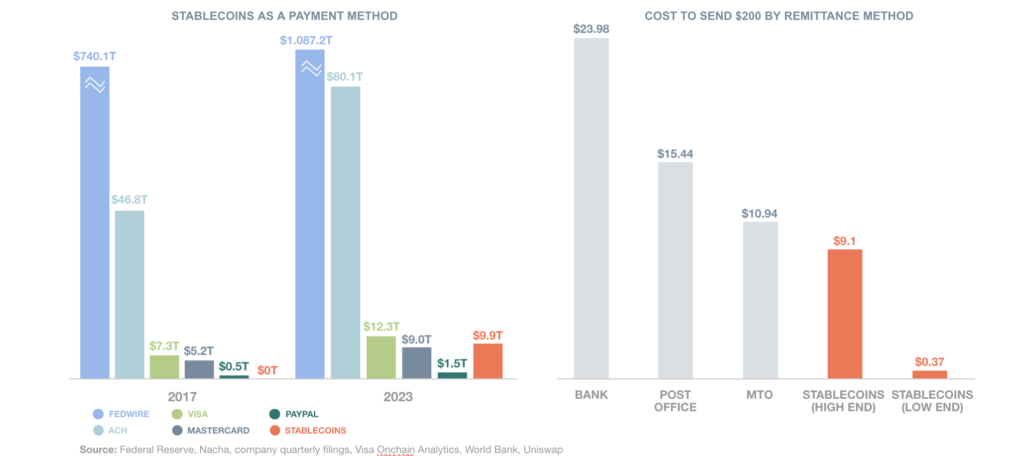

In Brazil, card settlement typically takes 30 days, while higher merchant discount rates lead to higher interchange take rates for card transactions — 2.9 percent for credit and 1.6 percent for debit. In the US, those rates hover around 1-3 percent and 0.25-1 percent respectively. An incentive therefore exists to push Brazilian merchants towards Pix, while their American counterparts have no such incentive. Boleto, a printed cash voucher, is another popular Brazilian payment method, and costs less to accept but takes a lot longer to process, and is inconvenient for users to pay.

Compared to those two options, Pix offers drastic improvements on all fronts: higher conversion, cost reductions, and faster settlements. Cost alone is not a strong enough incentive for American merchants to adopt FedNow. Looking forward, RTP providers will have to rethink the overall merchant and customer experience including conversion, loyalty, and customer satisfaction.

Bank incentives: Hopping the revenue hurdle

Real incentives already exist for banks to participate in RTP networks. There are cost savings from a reduction in the handling of checks and cash, including ATM usage. However, some banks harbor concerns that FedNow will cannibalize revenue from other payment methods, such as wire and credit card interchange fees, because the RTP option will tend to be cheaper. It is true that in countries with high RTP adoption rates, like Brazil, high interest rates and the ubiquity of installment payments (the original BNPL) mean fewer consumers carry credit card balances. This means that the loss of credit card revenue is not as high for Brazilian issuers as it might be in the US.

However, businesses and consumers have a strong preference for speed. “Pseudo-RTP” players like Venmo, Cash App, and Zelle are useful early indicators of demand for the real thing — and Zelle is on pace to reach $1T in run-rate volume by the end of this year. Meanwhile, as FedNow adoption grows among financial institutions, there are big opportunities for fintech startups to help FIs with hurdles like authorized push payments (APP) fraud, instant reconciliation, and ERP integration.

Security is a moving target

Wherever RTP systems gain traction, crimes like social engineering fraud, scams, and even physical robbery associated with APP fraud rise as a result. In 2023, the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook counted around 1M phone robberies, with thieves tending to act on Fridays, giving them more time to drain accounts while banks are closed over the weekend. Once they’re in a victim’s phone, a thief can do everything from place an order via MercadoLibre’s one-click checkout to access bank accounts — the average Brazilian has 5.8 accounts per person — and Pix rails, along with the 800 or so fintechs connected to them.

Combatting APP fraud is a team effort. Google recently launched a new anti-theft feature for Android devices that locks Brazilian phone screens when its AI detects a theft. The Federal Reserve has developed a tool called ScamClassifier to help the payments industry improve scam reporting, detection, and mitigation. And startups are emerging to tackle fraud on a global scale, with TunicPay, Archer Protect, and SOS Golpe as just a few notable examples.

Tap-to-Pay could level the playing field for offline PoS payments

One of my predictions last year was that digital wallets would become the next battlefield in e-commerce and at the point of sale, and that has become more and more true over the last year. At last count, digital wallets were the leading e-commerce payment method in the US, accounting for 37 percent of all e-commerce transactions (Asia Pacific at 70 percent and China at 82 percent), while credit card came second at 32 percent, and debit card a distant third at 19 percent.

However, digital wallets lag at physical points of sale (15 percent of total transaction value) because of the lack of interoperable QR codes, and other sources of friction. After all, it’s a laborious process to open your banking app, enter credentials, and scan a QR code while a cashier waits. Tap-to-pay technology would level the playing field for real-time payments, reducing the whole process to a single step — just like swiping your credit card. For now, though, issues like dispute management, instant refunds, and reconciliation still need to be solved.

Tap-to-pay has some big tailwinds at its back right now. Earlier this month, as part of the anti-competition settlement, the EU just accepted Apple’s offer to enable near-field communication (NFC) features for non-Apple wallet systems on Apple devices, including tap-to-pay. It also includes Face ID biometric authentication, defaulting for preferred payment apps, and a dispute settlement mechanism. And in the same month, NFC Forum announced a new functionality called multi-purpose tap. With it, a customer in a store could tap their phone on a terminal that simultaneously pays for their goods, checks their ID if they’re buying age-restricted goods like alcohol, adds points to their loyalty account, and provides a digital receipt.

Overall, infrastructure is emerging to help merchants manage a customer’s whole shopping journey, generate more sales, and ultimately boost customer loyalty. Because remember: improved costs and settlement times alone are not enough to entice merchants or consumers to adopt the real-time payments enabled by FedNow.

Looking ahead, opportunities abound for fintech startups to build and partner with financial institutions to fight APP fraud, enable instant reconciliation, integrate ERPs, and build interoperability between payment systems. Wherever startups are helping FIs orchestrate a smooth implementation and onboarding of FedNow, we are eager to partner up.

Originally published on Forbes.