Sanjay Aggarwal reflects on our inaugural Robotics Invest summit

Co-authored with Fady Saad of Cybernetix Ventures

The ideas outlined below come from the panelists, as summarized by our team taking notes on the day. To stay in touch, follow Robotics invest on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Last week, we welcomed some of the robotics industry’s leading entrepreneurs, investors, and operators to Boston for Robotics Invest, an invite-only summit packed with keynotes, panels, case studies, and robot demos.

We were very intentional in curating the speakers in these panels and, judging from the overwhelming response in the room, these discussions delivered. We’re extremely grateful to all our panelists for sharing their wisdom and experience with the group.

While the event itself was oversubscribed, we wanted to make sure everyone had the chance to access the insight, experience, and tactical advice that was available throughout the day. Luckily, our team was on hand to take notes. Here, we’ve summarized the key takeaways from each Robotics Invest panel conversation.

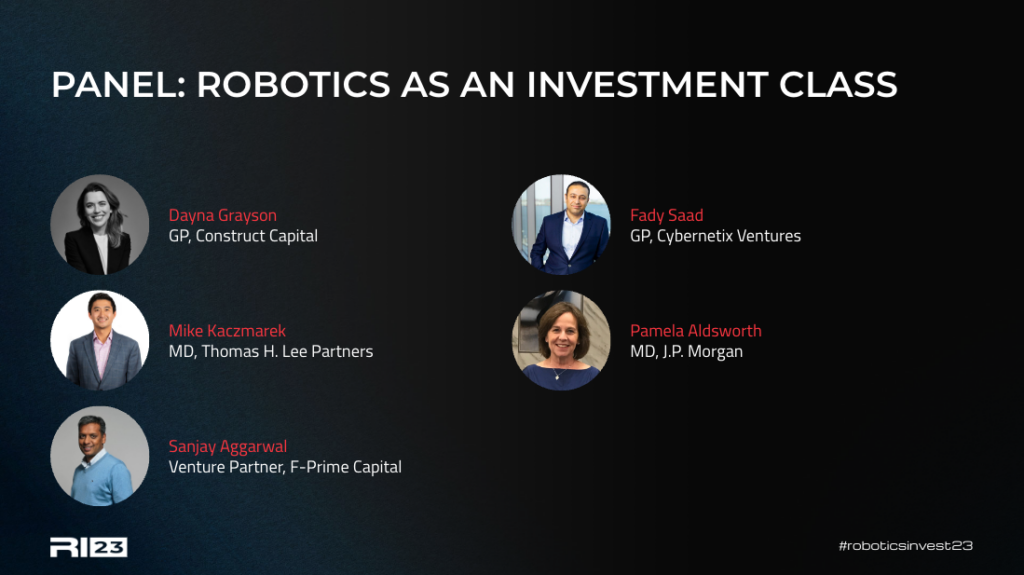

Robotics as an Investment Class

– Robotics sits in between two ends of the spectrum in the investing community: SaaS and biotech. This means that investors might look at robotics companies with a lens that may not fit, and try to optimize for metrics or markers for success that aren’t relevant for this category.

– Likewise, robotics companies often don’t follow the typical growth trend of your average SaaS business. For example, Kiva Systems spent three-to-four years with flat growth before it really took off.

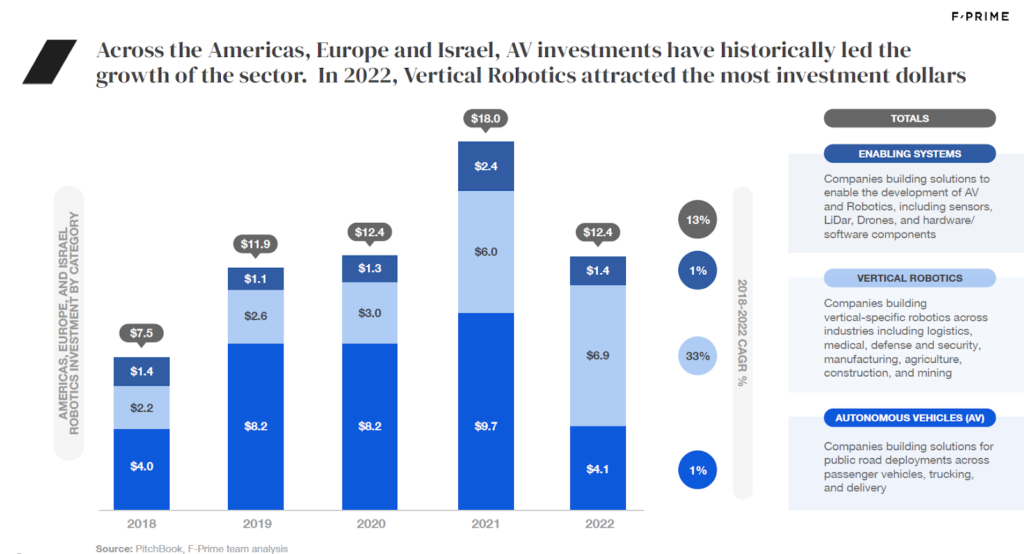

– We are still in the early days of robotics investment, especially when compared to the SaaS sector. The labor shortage is a secular issue, and the economy requires automation to keep up GDP growth.

– A solution’s lifetime value is an important metric in robotics, after factoring in capital and operational costs. Only looking at year-by-year margins may tell the wrong story.

– We are starting to see an evolution in financing models, which includes availability of equipment financing, which is helping to mitigate the capital costs of hardware.

– Revenue benchmarks aren’t as important for robotics companies at the Series A stage, nor is LTV/CAC. Instead, investors are looking for evidence that customers are moving beyond initial pilots and deploying the systems in production and at scale.

Building Product, Manufacturing & Supply Chain Strategies for Scale

– To succeed, robotics companies need to build great applications at the right time. For example, companies had tried to build cleaning robots in the 1990’s but the timing wasn’t right. And while matching macro conditions to the tech and value proposition is key, robotics companies should not let perfection trump a solution that’s “good enough.”

– Your first two hires should be a subject matter expert who can build the technology, and a subject matter expert who deeply understands the problem. Your first sales hire should be able to roll with the inevitable bugs and customer success issues, and be willing to go on this journey with you.

– Understand your technology’s core competency and be able to do that in-house. Everything else is an opportunity to outsource. However, you need to be careful about which tier of contract manufacturer you go with — if you don’t have a level of mind share with them, it can be hard to maintain the quality of your end product.

– Identify what’s essential and build it — over-engineering solutions is a common issue that can lead to cost escalation. It’s easier to add a feature in the future than take it away to reduce costs.

– There are a number of advantages to a Robotics-as-a-Service model. Reducing the capital intensity of an up-front sale can accelerate deployment, and you get a lot more customer engagement through the RaaS model. When a customer is evaluating your service’s value on a regular basis, you get a certain baseline of customer engagement.

Building a GTM Strategy for Scale

– Robotics startups should be talking to and incorporating the feedback of customers on day one. The transition to asking for payment can be tough and industry dependent — for example, contractors tend to pay their subcontractors when the job is done, and will not pay up front — so a pilot is usually necessary.

– Sales tend to fall apart when startups overpromise. Your timing needs to be realistic, and you must provide support over the longer term.

– The systems integrators flywheel can take a while to get going, and it’s not right for every use case. Startups at the very early stage should work directly with customers for design iteration. When you’re ready to deploy 10-99 units, a smaller system integrator (SI) can help customize the solution. And when you’re selling 100+, you’re ready for a larger SI like Dematic, Schaefer, or Honeywell.

– Lock-in long lead times on your supply chain early, and then design around them. You also need to be flexible and creative on how you source — for example, second-hand markets can be invaluable. As a general rule, designing around your supply chain up front can solve a lot of problems.

– Not all growth is good growth. The number one thing autonomous mobile robotics companies should work towards is a high number of customer relationships, and how you can expand the profitability for each. In other words, land-and-expand is critical.

Raising Money from Later Stage Investors

– The later stage is less aspirational than the early stage. The early stage is about selling the sizzle — the later stage is about selling the steak.

– Valuation matters, but it’s more important to focus on getting a fair valuation based on a business’ metrics, results, history, team, and other factors, rather than squeezing out the last dollar.

– Presenting realistic numbers is better than presenting spreadsheet projections that don’t make sense. Investors would rather see a credible number than an outsized revenue projection.

– Units matter more than revenue. Having credibility with customers and executing against your commitments matters, because it’s not just one transactional event.

– Investors want to be convinced that they’re investing in a team, not just one person. So showcase the team and let them present and answer questions during diligence.

– Diligence for later-stage investments involves talking to customers and getting conviction from them about whether they will do what the company says they will. Procuring customer references through videos or visits is a scalable solution here.

Role of Corporates in Start Up Innovation Landscape

– Corporates can provide access to markets and distribution networks, and build trust in early-stage companies by putting their weight behind their product and brand. However, startups must clear high risk and benefits bars during the evaluation process to land a potential partnership.

– FOMO does not necessarily enter into the equation, but if there’s a deadline to meet, the team will try to meet it as fast as possible.

– Large corporates have integration teams responsible for combining new technology into the company after mergers or acquisitions, while smaller companies may assign temporary teams for this task.

– To maintain relationships with corporates through different team members and priorities, early-stage companies should focus on key advocates and sponsors while also branching out to other stakeholders within different teams and functions.

– Corporate venture capital investments can offer access to expertise that would otherwise be costly, and accelerate regulatory timelines.

– Manufacturing experts from large corporates can help reduce costs by renegotiating contracts, playing hard ball with suppliers, and identifying alternatives.

Exiting a Robotics Business

– When it comes to exit strategy for startups, good communication channels are key in keeping options open. Founders should be proactive and keep everyone updated quarterly.

– Opinions are mixed on strategic investors. If you get the right partner, it gives your business model some validation. However, you want to limit your involvement with strategics if you have lots of options, as you don’t want to be limited to a single acquirer. Bottom line: either have multiple strategics on your cap table, or zero.

– The lifecycle of a robotics company can be up to 20 years, so plan for the long game.

– Personal relationships between board members and CEOs are more important than anything right now. A good board will have consistent and easy-to-pitch messaging for potential investors.

– The use of robotics is a long term secular trend that will not stop, and is accelerating with broader adoption and understanding of AI and machine learning.

To stay in touch, follow Robotics invest on LinkedIn and Twitter.